ANNOTATION: Taylor, Pamela G. and B. Stephen Carpenter, II. “Computer Hypertextual ‘Uncovering’ in Art Education.” Jl. Of Educational Multimedia and Hypermedia (2005) 14(1) 25-45.

In this work, authors Taylor and Carpenter explored the use of hypermedia in high school, as well as university undergraduate and graduate art education classes to explore ways that hypertext “uncovering” transforms the more traditional hands-on approach to teaching into a more minds-on discovery model. The authors draw from Wiggins and McTighe’s “teaching for understanding,” a somewhat traditional approach to education whereby learners “uncover” meaning through study as if it were a treasure waiting to be unearthed. Taylor and Carpenter build upon Wiggins’ work by suggesting that in artistic (and other) domains, the very unearthing process—looking at each shovelful to discover layers of meaning—is the learning event itself, not just a means to an end. The purpose of their paper is to show that hypertext models of learning, in which information is presented in an ill-structured, collagelike format, provides a better approach to arts learning and meaning-making than a traditional, linear learning structure because it better mimics one of the fundamental processes of art and art criticism, what aesthetician Arthur Danto (1992) describes as the process of not simply building upon but rather erasing the rules of what could be art to create something new. According to Danto, “… to understand [a work of art] requires reconstruction of the historical and critical perception which motivated it.”

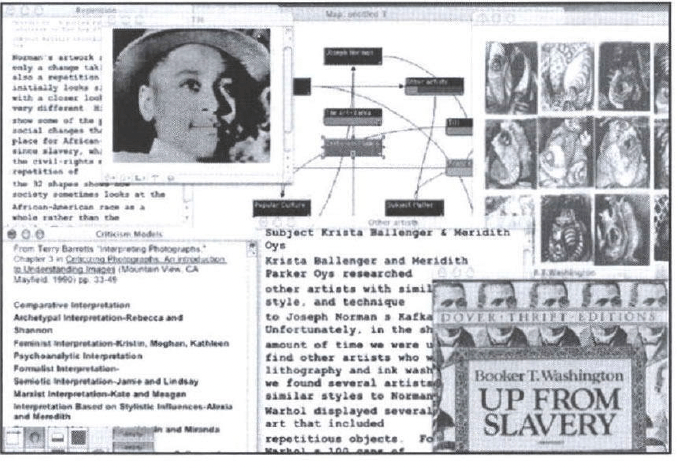

For method, Taylor and Carpenter used two forms of specially designed hypertext software to have students create collagelike visual hypertexts—visual “quilts” of information from which their subjects crafted visual representations of the connectedness of themes and ideas in a minds-on approach that mimics Danto’s goals of art criticism. Through two hypertext software applications—Storyspace and Tinderbox—they had students create hypertext documents to support research on an assigned art piece. The hypertexts became “manageable spaces where students can see and compare their notes, synopses, and ideas simultaneously.” They wrote, “The very messy, complex nature of hypertext may in fact be the key to its use as a successful educational approach in art education.” (p. 41) and that “computer hypertext may serve as a model for the kinds of divergent and inventive thinking integral to the study and making of art. Interactive computer hypertext is one way of seeing while exploring, of witnessing while performing, of correcting while blundering, and uncovering”—all practices critical to the creative, meaning-making experience. The research paper does not make clear how many students were involved in the “study” or whether a formal study was launched at all, nor does it make clear the time period during which their observations occurred. However, their paper does provide a useful set of informal observations and reflections on the use of the stated software in the authors’ own classrooms.

Taylor and Carpenter describe art criticism and by implication learning from art as a minds-on process by which the viewer looks actively and critically at what they see to uncover meaning. They point to hypertext learning as an excellent facilitator for this kind of learning, because it allows the learner to construct personal meaning from an ill-structured set of content, and thus create new perspectives. This echoes what has been suggested in other readings (Shapiro and Niederhauser, 2004) in that students who learn in a hypertext environment versus a traditional, linearly-organized format do not show a noticeable difference in their ability to identify and retain ideas and facts, but they do prevail when it comes to being able to connect, synthesize, and apply those ideas and facts in novel ways. They support Jonassen, Howland, Moore, and Marra’s (1999) argument that an ideal use for hypermedia (aka hypertext) as “primarily an environment to construct personal knowledge and learn with, not a form of instruction to learn from.” They describe this as a “liberatory” learning process that more closely imitates the inter-connective and naturally disorganized way that the mind works naturally, and thus it is ideally suited for artistic learning.

Additional Sources Cited:

Danto, A. (1992). Beyond the Brillo Box. New York: Noonday Press.

Jonassen, D. H., Howland, J., Moore, J. and Marra, R.M. (1999) Learning to solve problems with technology: A constructivist perspective (2nd ed.) Upper Saddle River, NJ: Merrill Prentice Hall.

Shapiro, A., & Niederhauser, D. (2004). Learning from hypertext: Research issues and findings. In D. H. Jonassen (Ed), Handbook of Research for Educational Communications and Technology (pp. 605-620). New York: Macmillan.

Wiggins, G. add McTighe, J. (1998). Understanding by Design. Alexandria, VA: Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development.