CITATION: OECD. (2019). Framework for the Assessment of Creative Thinking in PISA 2021 (Third Draft)

This is a long entry—much longer than I normally post—that in effect summarizes the PISA Creativity Framework, the theoretical foundation for an international test designed to assess creativity. This post begins with an overview of the assessment, then moves into a description and exposition of creativity as a human activity. Very interesting! Long, but definitely worth a read if you find the nature of creativity intriguing…

The Creative Thinking Framework is a product in active development by PISA, the Programme for International Student Assessment. It is a project of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), an international nonprofit organization that aims to establish evidence-based international standards for a range of social, economic, and environmental challenges, including education. PISA’s work on Creative Thinking is one of numerous projects that measure 15-year-olds’ ability to use their academic skills to meet real-life challenges. According to its website, “The PISA 2022 Creative Thinking assessment measures students’ capacity to engage productively in the generation, evaluation, and improvement of ideas that can result in original and effective solutions, advances in knowledge, and impactful expressions of imagination” across a range of contexts or domains.

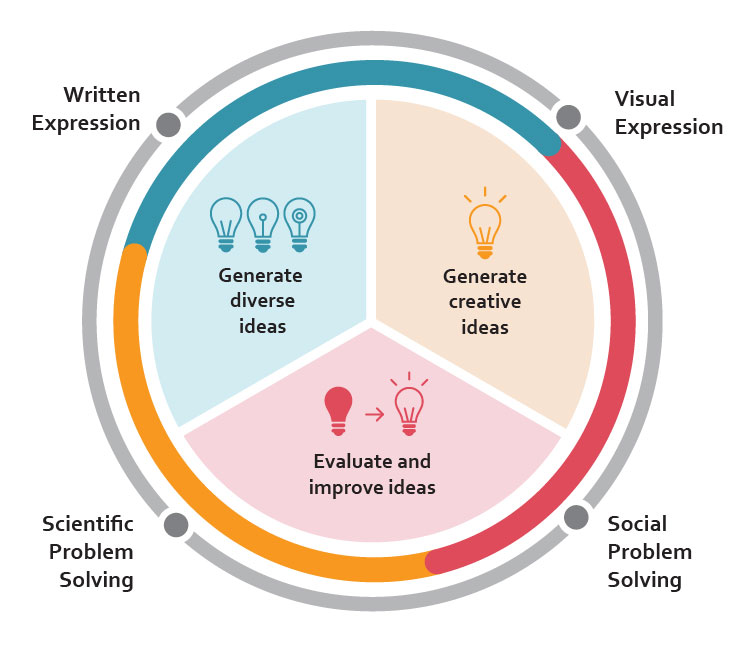

The third-draft framework presents the foundation for the design of the creativity assessment, a carefully crafted two-hour-plus test that uses a variety of means to measure creativity in four domains: written expression, visual expression, social problem-solving, and scientific problem-solving. In each domain, students complete open tasks that have no single correct response. They are either asked to provide multiple, distinct responses, or to generate a response that is not conventional. These responses can take the form of a solution to a problem, of a creative text, or of a visual artifact. The test is designed to provide policymakers a valid, reliable, and actionable measurement tool to help make evidence-based decisions in policy and pedagogy in compulsory/public schools.

When complete, the assessment will be provided to 15-year-olds in numerous countries as part of a larger 11-country study of ways to teach and assess creative and critical thinking. (It is unclear whether the assessment was delivered or not; it was supposed to happen in 2021, but was delayed to 2022 due to COVID. The website states, “The worldwide launch of the PISA 2022 Creative Thinking results will be held in 2024,” so presumably it did occur but I was unable to easily find any evidence as such.) PISA is designed not to single out creatively gifted individuals, but rather to describe the extent to which students are able to think creatively when expressing ideas, and then to relate this capacity to various aspects of school environment/systems. The assessment itself is comprehensive and well thought-out and is worthy of much consideration, but what is equally worthy of close consideration is the group’s theoretical foundation and its listing of evidence-based underpinnings of human creativity—and specifically, adolescent creativity.

The PISA assessment measures creativity in three primary domains:

- Creative Expression: This consists of both verbal and non-verbal forms of engagement, where individuals communicate their internal world to others. Verbal is written and oral; non-verbal is drawing, painting, modeling, music, movement, dance, drama.

- Knowledge creation: This is the advancement of knowledge where emphasis is placed on progress, not achievement—but improving upon existing ideas, better explanations or theories. It’s about reconstructing knowledge, reinterpreting the findings of others, or making new sense of existing theories.

- Creative problem-solving: Characterized by novelty, unconventionality, and persistence in solving complex problems.

The PISA framework is 55 pages long, including 10 pages of citations to support its every assertion. This literature review will summarize and condense the framework’s key evidence points and present in simpler form the fundamental evidence-based tenets of human creativity and creativity in education, but will not detail aspects of the assessment or its design. Citations are not consistently indicated below, but readers seeking more information are encouraged to review citations in the third-draft framework document, which is available on the PISA webpage.

Why assess creative thinking?

1) Societies depend on innovation to address emerging and increasingly urgent challenges in a rapidly changing world. 2) Improvements to creative thinking—engagement in the thinking processes connected with creative work—are associated with improvement in other thinking processes, metacognitive practices, identity development, problem solving, and career success and social engagement. 3) Developing an international assessment can help support changes in education policy and pedagogies.

What is education’s role in creative thinking?

Education equips students with the skills they need to succeed in society, and creative thinking is a broadly accepted key skill for success in the 21st century economy, in particular because it helps individuals adapt to a world that changes at lightning speed, thanks in large part to exceedingly rapid advances in technology as well as global environmental challenges that may require unforeseen skills to address. Schools play an important role in helping young people identify and develop their unique talents. Creative thinking can help students interpret experiences and events in personally meaningful ways, and it has shown to be of particular assistance to students who show little interest in school. Creative thinking is not a fixed “personality” asset, but rather something that can be developed over time—and teachers need tools to help teach it to their students through a variety of content areas.

What is creative thinking?

PISA’s definition is explicitly designed to apply to 15-year-old students around the world. They define it as, “the competence to engage productively in the generation, evaluation, and improvement of ideas, that can result in original and effective solutions, advances in knowledge, and impactful expressions of imagination.” Most interesting is that they define it as a competency, not an immutable personality trait. A second definition they cite from Plucker, Beghetto, and Dow (2004), is worth noting, as it highlights the social nature of creativity: “the interaction among aptitude, process, and environment by which an individual or group produces a perceptible product that is both novel and useful as defined within a social context.”

Following from the creative thinking is the creative product. The product piece requires a set of attributes and skills, including “intelligence,” domain knowledge, and or artistic talent—which I would refer to as technical abilities to bring to life what is a reflection of an inner vision—what PISA calls, “the expression of one’s inner world.”

There is a differentiation between Big C creativity and little c creativity. Big C creativity is associated with technology breakthroughs or artistic masterpieces—evidencing that the creative thinking must be paired with significant talent (talent, being a somewhat problematic term… I might choose “skill” because it is something that can and must be developed), deep expertise, and high levels of engagement—and the recognition from its ambient society that the product has value. Little c creativity refers to more everyday tasks: cooking a great meal without a recipe, scrapbooking, problem solving in scheduling at work. The literature suggests that little c creativity can be developed with education and training, and thus focuses its assessment on that aspect of creativity. It does not focus on Big C creativity, because there is a presumption that that level of creativity relies on some sort of innate, “God-given” talent or high intelligence. The development of little-c creativity matters in education because it can lead to not only the expression of one’s inner world (the arts), but also to other areas where idea generation matters, such as investigating answers to issues, problems, or society-wide concerns.

Domain specificity or generality

Researchers have long debated questions about domains: Is creativity domain-specific or are creative people creative in all domains? Is creative thinking different in science than it is in the arts? Early researchers (1950s) assumed it was not different, but more recent research (2011-20xx) suggest that creativity is indeed domain-specific.

Domains of creative engagement

How many domains are there? Researchers have repeatedly tried to categorize creative domains, notably among them J. Kaufman. His most recent work distinguishes five domains: everyday, scholarly, performance, scientific, and artistic. Others have reported similar groups, and most distinguish between scientific and artistic, but instead suggest problem solving, verbal, artistic, maths. Verbal and artistic were found by Conti to have no correlation whatsoever. Meta-analysis of empirical studies support that math/science and artistic/other forms of creativity are consistently distinct.

Confluence approaches of creativity

Confluence approaches (Amabile, Lucas) describe creative thinking as multi-dimensional, involving four components necessary for an individual to produce creative work: domain-relevant skills, creativity-relevant processes, task motivation, and a conducive environment. Sternberg and Lubart’s “investment theory of creativity” suggest six dimensions: intellectual skills, domain knowledge, thinking style, motivation, specific personality attributes, supportive environment. Sternberg later showed that the varied degree of each of these individual elements leads to a variety of outcomes.

Understanding and assessing creative thinking in the classroom

Confluence approaches acknowledge the importance of a combination of internal and environmental resources for successful creative engagement. As such, attending to the everyday school environment is important for ensuring creative development in the schools. Schools can nurture creativity by developing a variety of skills: cognitive skills, domain skills, openness to new ideas, willingness to collaborate, persistence, self-efficacy beliefs, and task motivation.

Social environments conducive to enabling creative development are: classroom culture, the educational approach of schools or school systems, the broader cultural environment. All of these influence the way students value creative ingenuity. Schools provide a helpful “habitat” for creativity conducive to measurement and assessment, and the school environment, as it sits within the system and the culture, enables the way in which individual creative motivations are developed and refined.

Individual Enablers of Creative Thinking

Cognitive Skills

Guilford’s 1956 concepts of convergent and divergent thinking have influenced creativity research. We might describe convergent thinking as “algorithmic,” whereas divergent thinking refers to the ability to produce novel ideas from unexpected combinations of available information. Most measures of creative thinking to date have focused on assessing levels of divergent thinking processes, but research has also shown that convergent thinking can also contribute to creativity. In other words, creative individuals who can think outside the box also show evidence of knowledge and skills from an “inside the box” perspective.

Domain Readiness

This means that individuals require some degree of skill and prior knowledge within a domain to produce creative work. However, this is neither universal nor linear. In some individuals, knowing the rules within a domain can block creative attempts to break them.

Openness to experience and intellect

The likelihood that an individual who “knows the rules” will be willing to break them depends on personality traits that many studies have shown characterize creative people—openness to ideas and openness to experience. Openness was shown to be the only “Big Five” personality traits that consistently applied to creative people, and this was validated across several cultures and countries. Divergent thinking also has been shown to positively correlate with openness. Other researchers have found that openness-related traits such adventurousness, willingness to be “uncomfortable” and curiosity for noveltly also apply to creative individuals.

Goal orientation and creative self-beliefs

Individuals who think they are creative tend to be more creative, coupled with persistence and perseverance. Efforts to stimulate creative thinking in the classroom should aim to help students believe in their own abilities and teach the value of consistent, sustained effort.

Collaborative engagement

Contemporary thinking is looking beyond creativity as an individual construct more toward a collective endeavor. Research is looking at the benefit of collaboration and teams in developing creative ideas. “Through collaborative engagement, teams can provide new answers to complex problems that are beyond the capabilities of any one person.” (Warhuus et al, 2017) Being able to engage in dialog and idea sharing creates fertile ground for the growth of new ideas. Schools can stimulate creativity in individuals by allowing for classroom collaborations that will engender new knowledge.

Task motivation

Much research supports the role of task motivation in creative productivity. Motivated individuals find their work meaningful, enjoy the work, desire to be challenged, and are relatively immune to outside pressures. This is related to the concept of a “flow” state in which an individual is lost in the single-minded desire toward its creative product.

Social enablers of creative thinking

Cultural norms and expectations

Cultural norms and expectations can shape the skills and knowledge that individuals prioritize. They can also encourage creative thinking in some situations, but discourage it in others. Several studies have concluded that a culture’s sense of individualism vs. collectivism has a significant impact on creative outputs of individuals.

Educational approaches

Classroom environments can stimulate and encourage creativity by increasing the rewards and decreasing the social costs associated with creative thinking. They must release emphasis on standardization and assessment.

Classroom climate

Informal feedback, goal setting, positive challenges, teamwork, autonomy, and recognition and encouragement all enable creativity. Harsh criticism, focus on status quo, low-risk attitudes, and high time pressure stymie creativity. School poliices that can inhibit creativity include: 1) only one right way/answer, 2) submission and authoritativeness, 3) adherence to lesson plans at all costs, 4) promoting the belief that originality is rare, 5) promoting beliefs in compartmentalization of knowledge, 6) discouraging curiosity and inquisitiveness, and 7) never letting learning be fun. Teachers are more likely to promote creativity in their classroom if the larger school/system values innovation. Important traits for teachers to stimulate: risk taking, idea diversity, collaboration with peers. Teachers must believe that creative thinking is a competency that can be developed in the classroom.

Teachers can encourage creativity by allowing students to set their own goals, monitoring progress, identifying promising ideas, and taking collective responsibility for productive, creative team work. They also need to teach students to distinguish when creativity is appropriate.

Creative engagement

Creative products provide indicators of creative thinking; these products can be used to determine the level of creativity in their thinking. Based on a variety of research, products are deemed creative when they are novel and useful as defined within their social context. In school, creative engagement takes the form of expression thru writing, drawing, music, or the arts; new knowledge and understanding; creative solutions to problems.

Key Points in Assessing Creativity: Implications for the PISA 2021 creative thinking assessment design

The following points are drawn from the frameworks’s implications section and are listed here because they are key in determining any student’s creativity:

- Key points for measuring/assessing creative expression: originality, aesthetics, imagination, affective intention (emotional expressiveness) and response

- Creative writing (whether fiction or nonfiction) is an expression that requires both cognitive and communication skills, logical consistency, details, and continuity.

- Visual expression requires that students communicate ideas using visual media and helps students decode both overt and subtle images. Visual communication is increasingly important in a digitized world.

- Social problem solving. This develops skills in understanding and address the needs of others to find solutions to key problems.

- Creative scientific problem-solving focuses on the generation of new ideas, rather than on applying taught knowledge.

The Competency Model of Creative Thinking

This graphic indicates the competencies of creative thinking in four major domains; this illustrates the assessment areas that PISA covers.

- Generate diverse ideas: How many solutions or ideas can an individual generate? Also referred to as “ideational fluency.” Also, how diverse are those ideas? AKA “ideational flexibility.”

- Generate creative ideas: As compared to what—new to you, or new to the larger population? The assessment compares uniqueness in the context of the population taking the test. To what extent does the student draw upon multiple domains in solving a complex problem or generating new ideas?

- Evaluate and improve ideas: Creativity is not always about deviating from the usual, but rather novel ideas that are effective for intended purpose. Can the student identify limitations and solutions to improve them?

Final key points regarding assessing creativity.

The PISA creativity assessment itself is coupled with a survey designed to determine each student’s engagement with four categories of creative “enablers.” These are measured by self-report. The contextual factors for creativity as covered in this survey are:

- Curiosity and exploration: Individuals’ creativity is affected by individual curiosity, their openness to new experiences, and their disposition for exploration.

- Creative self-efficacy: Do students believe in their own creativity? How confident are students about their ability to think creatively in different domains?

- Beliefs about creativity: Do individuals believe that they can be trained, or that creativity is an immutable personality trait? Do they think creativity only exists in the arts? Do they believe it’s a good thing in all contexts?

- Creative activities in the classroom and school: Do students participate in school activities and out-of-school that require and develop their creative capacity? Are they regularly asked to perform or generate new ideas?

- Social environment: Is free expression encouraged? Do authority figures (teachers) take students’ new ideas seriously? Does the larger environment value novelty and expression?